AUTHORS: Yali Pang, Nakeina E. Douglas-Glenn, Cameron Williams

February 2025

INTRODUCTION

The minimum wage in the U.S. is a federally mandated baseline introduced in 1938 under the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) to ensure workers' basic standard of living. The FLSA established essential worker protections, including a federal minimum wage, overtime payment, and child labor ban.[3] Today, the FLSA requires that nonexempt employees, regardless of state (with few exceptions), make a minimum wage of $7.25 per hour. This rate has not changed in 16 years since 2009. Many states, cities, and counties have enacted their own minimum wage laws, often setting wages higher than the federal minimum wage to better align with the cost of living in local areas. More than 20 states and nearly 40 local jurisdictions increased their minimum wage rates in 2024, bumping wages for 9.9 million workers, according to the Economic Policy Institute (EPI).[4] At the beginning of 2025, 21 states raised their state minimum wages. The minimum wage is crucial in reducing poverty and income inequality by providing a safety net for the lowest-paid workers.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- The federal minimum wage has not changed in the past 16 years. Over one-third of states still use the federal minimum wage today.

- Low minimum wage has profound negative impacts on individuals and society.

- The low minimum wage disproportionately impacts women, people of color, young workers, and less educated workers, making it hard for them to secure living essentials with the increasing cost of living.

- Increasing the minimum wage has economic and social benefits, lifting workers out of poverty and reducing income inequalities.

TODAY’S WAGES

The current minimum wage has not kept up with productivity and the cost of living, leading to growing concerns about its effectiveness and debates regarding policy reforms. Despite its increases since 1938, the federal minimum wage has significantly fallen behind inflation, productivity growth, and increased living costs. According to the Center for Applied Research on Work at Cornell University, if the federal minimum wage had increases with productivity, it would have been about $25.52 an hour in 2024, which is over three times the current rate.[5]

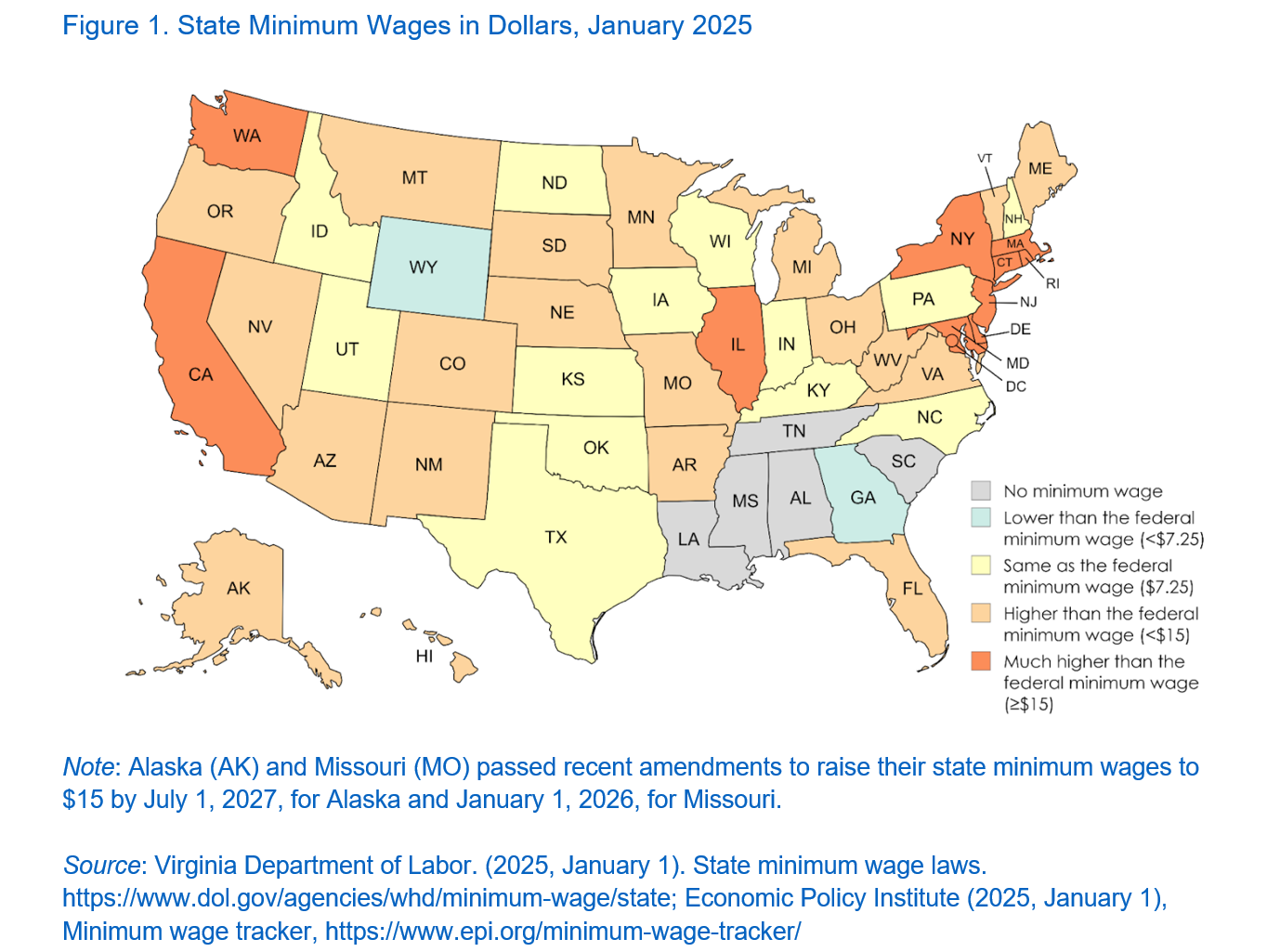

State minimum wage laws vary widely, reflecting different priorities and economic conditions across the country (Figure 1). Washington, D.C., has the highest minimum wage of $17.50. Ten states (CA, CT, DE, IL, MA, MD, NJ, NY, RI, and WA) have minimum wages of $15 per hour or higher. There are 20 states (AK, AR, AZ, CO, FL, HI, ME, MI, MN, MO, MT, NM, NE, NV, OH, OR, SD, VA, VT, WV) with a minimum wage above the federal level but less than $15. Thirteen states (ID, IN, IA, KS, KY, NH, NC, ND, OK, PA, TX, UT, and WI) adhere to the federal minimum wage. Two states (GA and WY) have a minimum wage lower than the federal minimum wage. Today, five states (AL, LA, MS, SC, and TN) still do not have a minimum wage law. When the minimum wage does not keep pace with productivity growth, workers earning low wages find it difficult to purchase essential goods and services. This struggle results in stagnant or declining living standards, particularly during periods of inflation. The wage disparity predominantly impacts marginalized workers, further widening economic inequalities.

NEGATIVE IMPACTS OF LOW MINIMUM WAGES

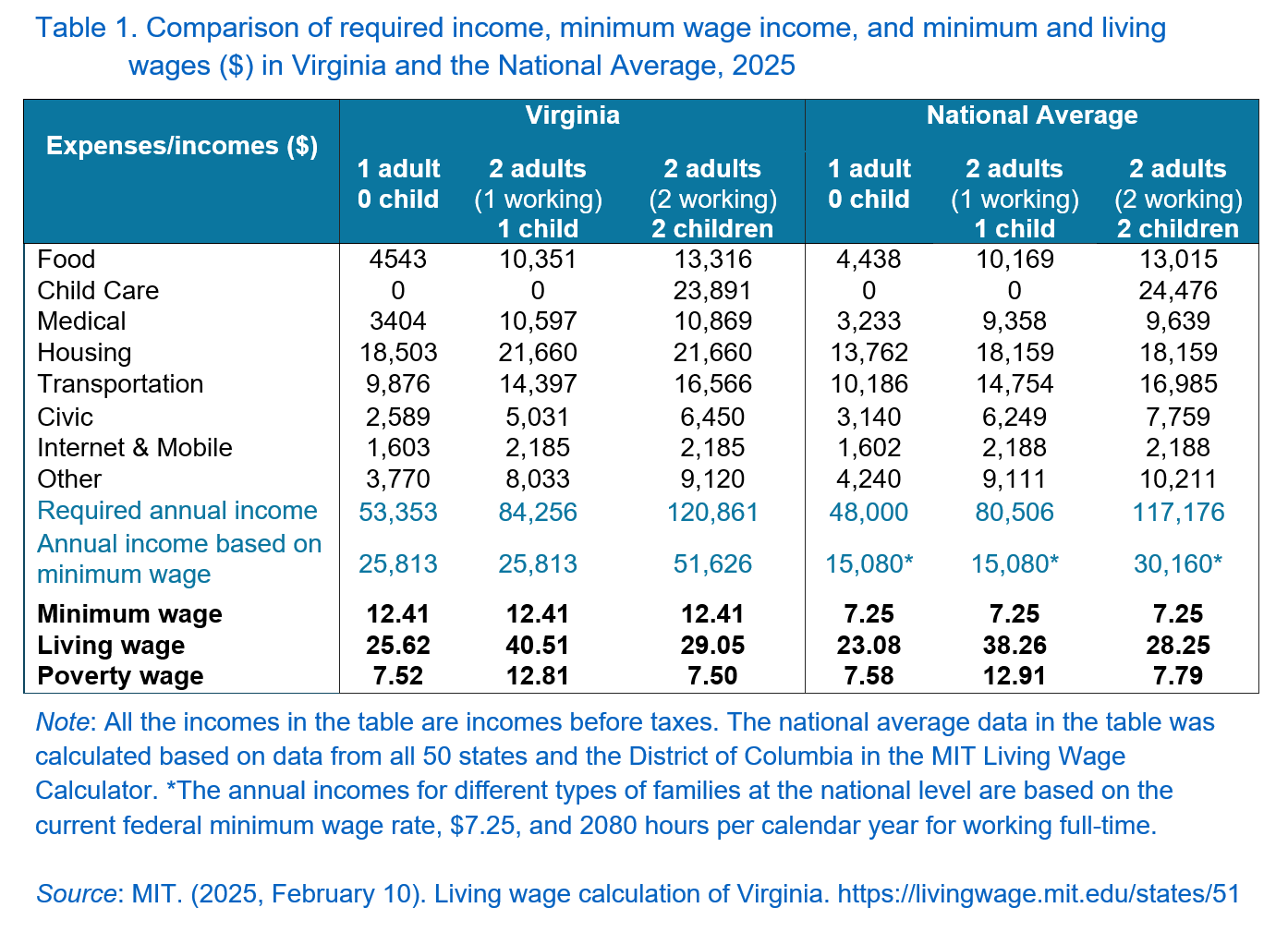

Low minimum wages significantly impact individuals and society. At the individual level, a minimum wage lower than the hourly wage a person needs to afford shelter, food, and essentials (i.e., living wage), directly impacts the quality of life for low-income workers and their ability to afford basic needs. Today, the annual income based on the minimum wage is frequently lower than the required annual income based on the living wage at both the state and national levels. For example, Table 1 lists all the essential costs for families of different sizes in Virginia. The required living wage before taxes to cover essential needs is estimated at $53,353 for one adult without children, $84,256 for a two-adult family (one working) with one child, and $120,861 for a two-adult family (both working) with two children in 2025. However, based on the state minimum wage, a single working adult's annual income is just $25,813, less than half (48.4%) of the required annual income for one adult without children and 30.6% of the required annual income for a two-adult family (one working) with one child. This disparity is also evident at the national level, leaving minimum wage earners to seek additional resources or choose between essential needs to cover their basic needs.

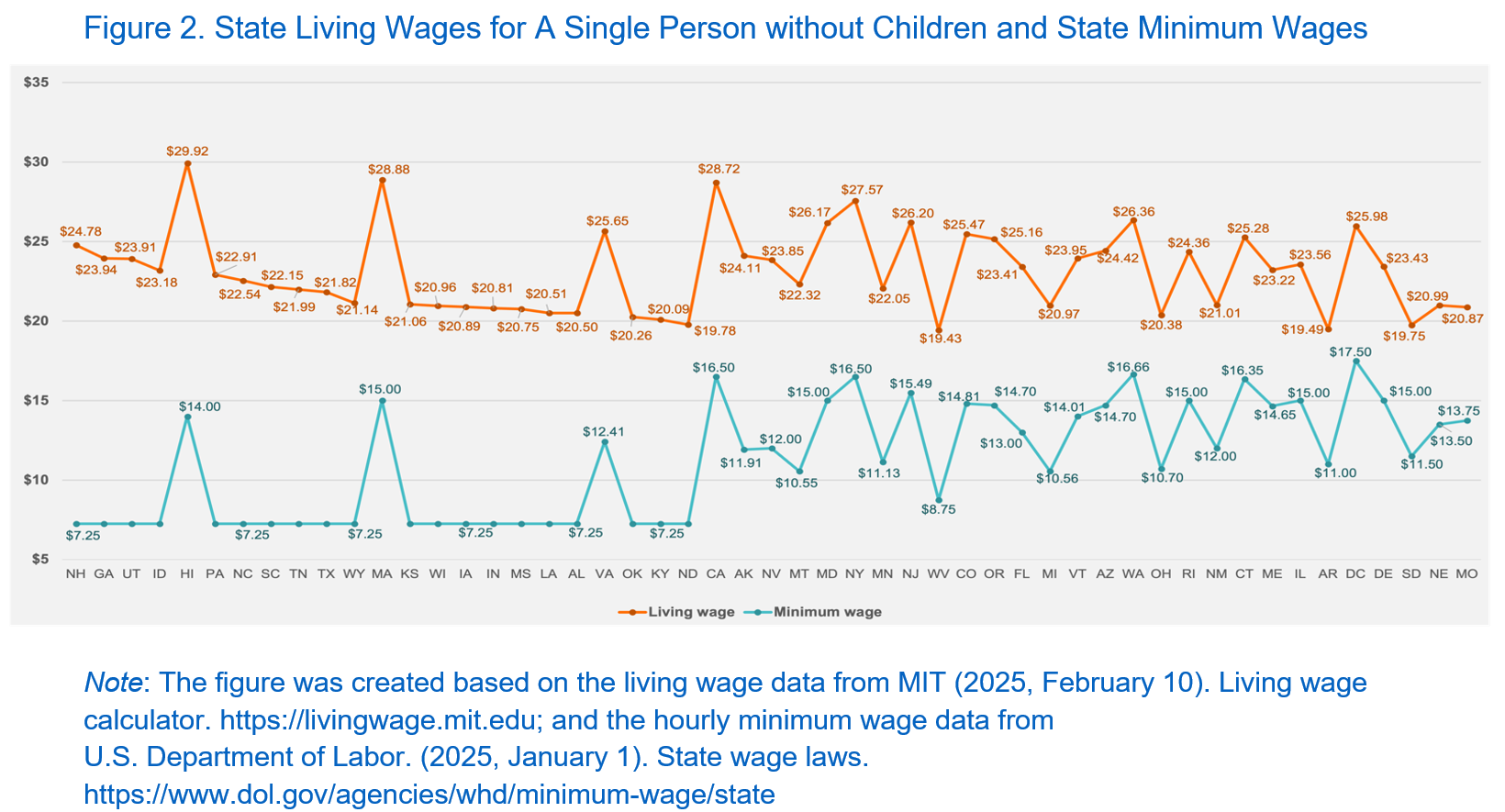

The gap between the hourly minimum wage and the living wage highlights the financial challenges workers face (Figure 2). The states with the largest wage gaps, Georgia, New Hampshire, and Utah, fall below a living wage by more than $16.00 per hour. Seven states (ID, HI, NC, PA, SC, TN, and TX) have a wage difference between $14.00 and $15.99, followed by 15 states (AK, AL, CA, IA, IN, LA, MA, MS, ND, KS, KY, OK, VA, WI, and WY) with a difference between $12.00 and $13.99, 11 states (CO, FL, MD, MI, MN, MT, NJ, NV, NY, OR, and WV) with a difference between $10.99 and $11.99, and 15 states (AR, AZ, CT, DC, DE, IL, ME, MO, NE, NM, OH, RI, SD, VT, and WA) where the gap is less than $10.00. Notably, about 80% of the 25 states with wage differences over $12.00 adhere to the federal minimum wage.

The gap between the hourly minimum wage and the living wage highlights the financial challenges workers face (Figure 2). The states with the largest wage gaps, Georgia, New Hampshire, and Utah, fall below a living wage by more than $16.00 per hour. Seven states (ID, HI, NC, PA, SC, TN, and TX) have a wage difference between $14.00 and $15.99, followed by 15 states (AK, AL, CA, IA, IN, LA, MA, MS, ND, KS, KY, OK, VA, WI, and WY) with a difference between $12.00 and $13.99, 11 states (CO, FL, MD, MI, MN, MT, NJ, NV, NY, OR, and WV) with a difference between $10.99 and $11.99, and 15 states (AR, AZ, CT, DC, DE, IL, ME, MO, NE, NM, OH, RI, SD, VT, and WA) where the gap is less than $10.00. Notably, about 80% of the 25 states with wage differences over $12.00 adhere to the federal minimum wage.

These low minimum wages exacerbate financial difficulties and other challenges for workers, leading to job insecurity, family instability (e.g., divorce), unaffordable childcare, and unhealthy living conditions, all of which perpetuate poverty.[6] Increasing the minimum wage can effectively promote equity by allowing productivity increases to benefit a wider segment of society economically and socially.

THE CASE FOR RAISING THE MINIMUM WAGE

Over half of minimum wage workers are part-time employees who often lack health insurance, paid time off, or sick leave, which could lead to significant financial burdens, high levels of stress, and health problems.[7] Research links low-income levels with higher rates of mental illness, smoking, and suicide attempts.[8] Additionally, low wages limit individuals' financial freedom and heighten their dependence on government assistance. In 2019, 74% of people living at or below 200% of the federal poverty line relied on public aid, such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) or Medicaid, to meet their basic needs.[9] According to the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), almost one-third of SNAP households have earned some income; however, only 20% of these households have gross monthly income above the federal poverty line.[10] The average SNAP household’s monthly gross income is $872, and net income is $398. In general, approximately 60% of workers in the lowest wage bracket (earning less than $7.42 per hour) received some form of government assistance, either directly or through a family member, while more than half (52.6%) of workers in the second lowest wage bracket (earning between $7.42 and $9.91 per hour) also received public assistance.[11] This dependence on assistance and the inability to save for emergencies or major purchases reinforces a cycle of poverty that hinders financial independence.

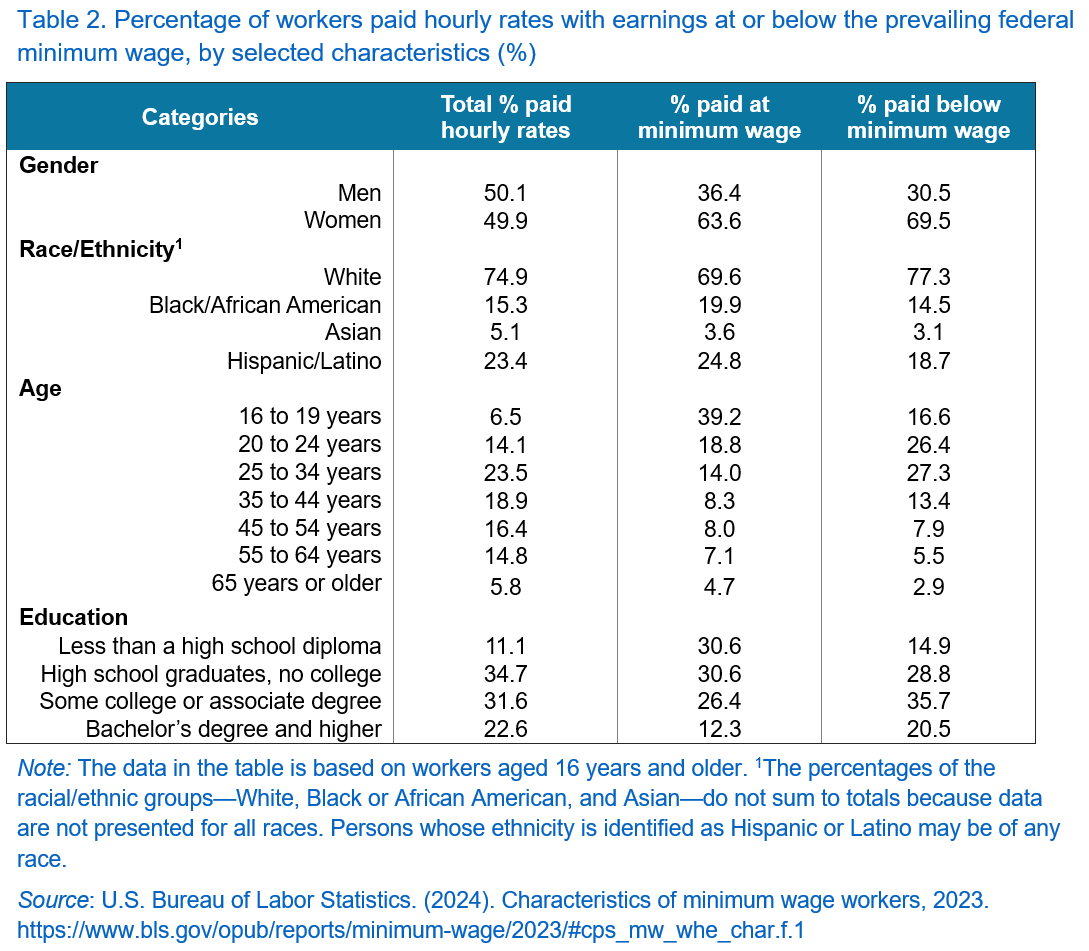

Low minimum wages exacerbate the inequities experienced by women and people of color.[12] Women and people of color are disproportionately represented among minimum wage earners. In 2023, women accounted for 63.6% of minimum wage workers compared to 36.4% of men, despite comprising only half of all hourly employees.[13] Similarly, Hispanic/Latino (23.4%) and Black/African American (19.9%) workers were overrepresented among minimum wage earners (see Table 2).

Low minimum wages also affect young workers and those with lower education levels (see Table 2).[14] Workers aged 16 to 19, who represent only 18.7% of all hourly workers, make up 39.2% of minimum-wage earners. Those without a high school diploma account for 11.1% of all hourly workers but make up 30.6% of workers paid at minimum wage; high school graduates without a college degree make up 34.7% of all hourly workers and 30.6% of workers paid at minimum wage; and people with some college or an associate degree account for 31.6% of all hourly workers, but 35.7% of those paid below minimum wage.[15] People with multiple intersecting identities (e.g., gender, race, age, and education), such as older workers with low education, and single mothers of color with low education, experience more severe negative impacts of low minimum wages, making it harder for them to improve their living conditions.[16]

Estimates suggest that increasing the federal minimum wage to $15 per hour in 2025 would raise the earnings for about 32 million workers, about 21% of the workforce. Of those impacted workers, at least 19 million are essential and front-line workers, who often receive a lower wage on average and are disproportionately represented among socio-economically disadvantaged groups.[17] It would lift up to 3.7 million people out of poverty, ensuring more low-income workers can afford basic living expenses and achieve basic economic security.[18] Additionally, older and full-time workers, often the breadwinners of their families, are more likely to benefit from the increased minimum wage. The increased income would help them secure essential needs and services for their families, especially children, improving their quality of life.[19]

Beyond the vulnerable populations living at or below minimum wage levels, an additional challenge is the increasing number of workers to whom labor and minimum wage standards do not apply. For example, certain employee categories, such as tipped workers, workers with disabilities, and independent contractors, are excluded from the minimum wage standards in the FLSA.[20] Likewise, employers who obtain a certificate from the Wage and Hour Division are authorized to pay a wage less than the minimum wage to workers with disabilities for the work being performed.[21] The Full-time Student Program is allowed to pay students no less than 85% of the minimum wage.[22] An estimated 15% of workers are independent contractors such as freelancers, consultants, and gig workers; they are more likely to be men, Black and Hispanic workers, those aged 65 and over, and those with less education and are more likely to work multiple jobs or a few hours.[23] The low payment and lack of benefits related to nonstandard employment, especially for on-call and temporary workers, significantly impact their access to resources and services, opportunities for upward mobility, and overall family well-being.[24] Therefore, while raising the minimum wage would generate significant positive outcomes for millions of workers, the uncovered workforce remains an invisible, vulnerable group.

.png)

In 2025, at the national average, an adult without children requires an annual income of $48,000 before taxes to cover all essential needs. The required annual income is $80,506 and $117,176, respectively, for a two-adult family (one working) with one child and a two-adult family (both working) with two children. However, the annual income based on the current federal minimum wage rate ($7.25) is only less than one third of the required income for an adult without children, 18.7% of the required annual income for a two-adult family (one working) with one child, and 25.7% of the required annual income for a two-adult family (both working) with two children.

CHALLENGES & CONSIDERATIONS

Many business organizations and lawmakers oppose increasing the minimum wage, concerned that higher labor costs might compel companies to reduce jobs and increase labor expenses. A recent report by the Congressional Budget Office projected that while a raise in the federal minimum wage to $17 an hour by 2029 could reduce poverty, it might also result in the loss of hundreds of thousands of jobs, underscoring the complex economic trade-offs involved in adjusting minimum wage policies.[26] Others expressed concern that increasing the minimum wage could significantly raise a small business's labor expenses, potentially leading to layoffs or the adoption of labor-saving technologies.[27]

Conversely, others argue that increasing the minimum wage would benefit small businesses by boosting employee productivity, reducing turnover rates, and enhancing consumer spending.[28] In fact, a recent survey suggests that the majority (60%) of small businesses support increasing the minimum wage, even though they express concern about worker affordability.[29] Some studies indicate that increasing the minimum wage could generate additional inflation, especially during an economic boom, but the increase in inflation is very small.[30] Other research finds no impact of minimum wage increases on the inflation rate.[31]

Low minimum wages are costly for the individual, the government, and society. Lower minimum wages have high costs on the community, as government benefits and assistance programs such as Children's Health Insurance Program (CHIP), Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), and SNAP have a considerable price tag. For states with a minimum wage below $15, the federal government and their state governments spend about $254 annually on these programs, 42.1% ($107 billion) of these costs were to assist working families paid at a minimum wage or below minimum wage.[32] For businesses, productivity and retention rates for low-wage workers are low as they often manage a second job or are constantly looking for better opportunities.[33]

ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL BENEFITS OF RAISING THE MINIMUM WAGE

Raising the minimum wage would significantly alleviate poverty, improve family well-being, help reverse income inequality, and reduce social welfare expenses. Raising the federal minimum wage to $10.10 could decrease SNAP enrollment by 3.1 to 3.6 million people, saving nearly $4.6 billion in annual program expenditures.[34] This enables state and federal funds to be more efficiently directed toward the families most in need, making efforts to alleviate poverty more effective.[35] Higher wages also contribute to cost savings by improving community health through enhancing access to preventive care and improving access to higher-quality nutrition and food. This shift not only alleviates the fiscal burden on taxpayers but also redirects public funds toward other critical areas.

Increasing the federal minimum wage to $15.00 would directly affect 32.2 million workers, lifting many out of poverty. Data show that this increase would raise the earnings of approximately 31.3% of Black workers, 26% of Hispanic or Latino workers, and 18.4% of white workers.[36] About 19 million women would benefit from this increase, with 23.6% of white women, 30.7% of Hispanic women, and 34.0% of Black women receiving a direct or indirect pay raise.[37] A higher minimum wage would help reduce income inequality by ensuring fairer wages, benefiting those significantly underpaid.

A higher minimum wage would also benefit essential and front-line workers. Thirty-five percent of retail-sector workers and over half of restaurant workers would get a raise in their salaries. Over five million healthcare workers and those working in social assistance and education sectors would also see an increase in their earnings.[38] The increase in the salaries of these workers could lead to more educational opportunities, better health outcomes, and higher overall life satisfaction for low-income individuals and families, contributing to a more equitable society.[39]

POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS

Given the wide variation in wages across the country, multiple policy solutions can help ensure that workers receiving higher wages and the businesses that employ them are supported in the transition to higher wages. The recommendations focus on three key areas: adjusting minimum wage levels, expanding wage protections and public assistance, and supporting small businesses. Tying federal, state, and local minimum wage to essential living costs, inflation, and economic growth would help to maintain wage adequacy over time. Expanding minimum wage protection and public assistance coverage can complement these adjustments to ensure workers remain economically secure. Supporting small businesses can help them adapt to higher wages, mitigating financial strains while improving employment outcomes. These policy options create a more balanced approach that could significantly influence the conversation and reduce workers’ vulnerability.

- Establish a higher federal minimum wage. Establishing a higher, uniform minimum wage across all states will help standardize the income floor nationwide, reducing inequality and bolstering economic stability in lower-wage regions. Substantial increases in the minimum wage can be implemented without detrimental effects on employment and play a crucial role in alleviating poverty, especially among Black and Latinx communities.[40] The average living wage for a single person without children in the United States is about $23.08 per hour based on the living wages across 50 states and DC in 2025.[41] Increasing the federal minimum wage to at least $23.08 would help low-income workers afford their families' essential needs.

- Adapting the minimum wage to inflation. One solution to address wage erosion is to adapt the minimum wage to inflation. This approach would tie wage increases to inflation rates, ensuring the minimum wage keeps pace with rising living costs. Historically, the federal minimum wage has not been revised regularly to reflect inflation and living costs, resulting in stagnation relative to economic growth.

- Establish a state minimum wage that reflects the state’s cost of living. Workers should receive a wage reflective of their state’s cost of living. Even though 25 states and Washington DC have a wage increase this year, many states still follow the Federal minimum wage of $7.25. Implementing a state wage that reflects its cost of living (for example, establishing a minimum wage of $29.92 in Hawaii, $22.54 in North Carolina, and $25.28 in Connecticut) will help ensure that families can afford basic needs, access health, and other services, and secure education opportunities, thus improving their quality of life and family well-being in general.[42]

- Expanding minimum wage protections to the growing uncovered workforce. Expanding minimum wage protections and overtime pay eligibility is essential for promoting economic equity across various worker groups. The Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) does not consistently cover tipped workers, workers with disabilities, youth workers, and many misclassified or nonstandard workers, even though they are legally entitled to protection under the act. This leaves many workers without access to minimum wage. Extending these protections to all worker categories would help reduce wage disparities and ensure fair treatment.

- Expand public assistance benefits to close the minimum-to-living wage gap. Enhance benefit levels for minimum-wage workers by utilizing existing programs to facilitate implementation. For instance, expanding programs like the earned income tax credit, increasing childcare and housing assistance, and enhancing medical healthcare subsidies are viable options. Funding could be sourced from contributions by high earners and corporations, akin to Social Security and Medicare. Concentrating efforts here would alleviate the necessity gap for workers while easing employers' financial load to cover wage differences.

- Implement a cash transfer program. Providing a monthly universal or guaranteed income source to individuals and families could reduce financial volatility and stress. The premise is that it gives a small cash allotment that allows the recipient to make decisions about the expenses it covers. Recipients typically allocate funds to their most pressing needs like rent, childcare, groceries, and training. There are two main cash transfer models.[43] Universal basic income (UBI) would provide a no-strings-attached approach to shoring up monthly budgets for all members of society. Alternatively, a guaranteed income (GI) program addresses the needs of a small number of low-income residents who are most in need. According to the Guaranteed Income Pilot Dashboard, GI programs provide eligible participants with a monthly stipend, ranging from $200 to $1,000, for a duration of anytime from 10 to 24 months.[44] They have diverse funding sources such as private donations (e.g., Stockton Economic Empowerment Demonstration), government funding (e.g., Alaska Permanent Fund Dividend), and philanthropic funding (e.g., Magnolia Mother's Trust).[45]

- Establish a small business assistance program. Increasing the federal minimum wage would likely reduce reliance on public assistance programs, generating government savings. These savings could be reallocated to support the reported burden on small businesses as they transition to higher wages. A portion of the cost savings to federal supplemental programs could be allocated for wage adjustment loans, tax credits, or direct grants. This support could help offset higher payroll commitments, fund labor-saving technology, or associated operational efficiencies for qualifying small businesses.

CONCLUSIONS

The federal minimum wage has remained unchanged for 16 years, disproportionately impacting women, people of color, the less-educated, the low-income, and other vulnerable populations, making it difficult to secure life essentials, access basic services, and improve living conditions. Raising the minimum wage has broad economic and social benefits. Increasing the federal minimum wage to align with the current levels of productivity and to achieve a living wage would benefit millions of workers in the United States. In order to help reduce inequities caused by a low minimum wage, federal and local governments must collaborate to evaluate the cost of living, and the impacts of low minimum wages on different groups in order to establish a minimum wage reflecting local living costs.

REFERENCES

[1] Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2024, January). CPI inflation calculator. https://www.bls.gov/data/inflation_calculator.htm

[2] The living wage, $23.08 is calculated based on the minimum wage of all 50 states and DC for one adult without children. See more details in Table 1.

[3] Grossman, J. (n.d.). Fair labor standards act of 1938: Maximum struggle for a minimum wage. U.S. Department of Labor. https://www.dol.gov/general/aboutdol/history/flsa1938; Wage and Hour Division. (n.d.). History of changes to the minimum wage law. U.S. Department of Labor. https://www.dol.gov/agencies/whd/minimum-wage/history

[4] Hickey, S. M. (2023, December 21). Twenty-two states will increase their minimum wages on January 1, raising pay for nearly 10 million workers. Economic Policy Institute. https://www.epi.org/blog/twenty-two-states-will-increase-their-minimum-wages-on-january-1-raising-pay-for-nearly-10-million-workers/

[5] Baker, D. (2020, January 21). This is what minimum wage would be if it kept pace with productivity. Center for Economic and Policy Research. https://cepr.net/publications/correction-this-is-what-minimum-wage-would-be-if-it-kept-pace-with-productivity/

[6] Fuller, J., & Raman, M. (2023). The high cost of neglecting low-wage workers. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2023/05/the-high-cost-of-neglecting-low-wage-workers; Cherlin, A. (2014). Labor’s love lost: The rise and fall of the working-class family in America. Russell Sage Foundation. https://www.russellsage.org/publications/labors-love-lost; Malik, R. (2019, June 20). Working families are spending big money on child care. Center for American Politics. https://www.americanprogress.org/article/working-families-spending-big-money-child-care/; Leigh, J. P., & Du, J. (2018, October 4). Effects of minimum wages on population health. Health Affairs. https://www.healthaffairs.org/content/briefs/effects-minimum-wages-population-health

[7] Malik, R. (2019, June 20). Working families are spending big money on child care. Center for American Politics. https://www.americanprogress.org/article/working-families-spending-big-money-child-care/; Leigh, J. P., & Du, J. (2018, October 4). Effects of minimum wages on population health. Health Affairs. https://www.healthaffairs.org/content/briefs/effects-minimum-wages-population-health

[8] Sareen, J., J G Asmundson, G., McMillan, K., Afifi, T. O., & McMillan, K. A. et al. (2011). Relationship between household income and mental disorders: Findings from a population-based longitudinal study. Arch Gen Psychiatry, 68(4), 419-427. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.15

Alloush, M. (2022). Income, psychological well-being, and the dynamics of poverty. Hamilton College. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4008136

Sherman, A., & Mitchell, T. (2017, July 17). Economic security programs help low-income children succeed over long term. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. https://www.cbpp.org/blog/economic-security-programs-help-low-income-children-succeed-over-long-term

[9] Macartney, S., & Ghertner, R. (2023, January 20). How many people participate in the social safety net? U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/18eff5e45b2be85fb4c350176bca5c28/how-many-people-social-safety-net.pdf

[10] Cronquist, K. (2021). Characteristics of supplemental nutrition assistance program households: fiscal year 2019 (No. SNAP-20-CHAR; p. 144). US Department of Agriculture. https://fns-prod.azureedge.us/sites/default/files/resource-files/Characteristics2019.pdf

[11] Cooper, D. (2016). Balancing paychecks and public assistance (Briefing Paper No. 418). Economic Policy Institute. https://www.epi.org/publication/wages-and-transfers/

[12] U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2024). Characteristics of minimum wage workers, 2023. https://www.bls.gov/opub/reports/minimum-wage/2023/

[13] U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2024). Characteristics of minimum wage workers, 2023. https://www.bls.gov/opub/reports/minimum-wage/2023/

[14] U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2024). Characteristics of minimum wage workers, 2023. https://www.bls.gov/opub/reports/minimum-wage/2023/

[15] U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2024). Characteristics of minimum wage workers, 2023. https://www.bls.gov/opub/reports/minimum-wage/2023/

[16] Belman, D., Wolfson, P., & Nawakitphaitoon, K. (2015). Who is affected by the minimum wage? Industrial Relations: A Journal of Economy and Society, 54(4), 582-621. https://doi.org/10.1111/irel.12107

[17] Koebe, J., Blau, F., & Meyerhofer, P. (2022, March 22). Essential and frontline workers in the covid-19 crisis (updated). EconoFact. https://econofact.org/essential-and-frontline-workers-in-the-covid-19-crisis

[18] Cooper, D., Mokhiber, Z., & Zipperer, B. (2021a). Raising the federal minimum wage to $15 by 2025 would lift the pay of 32 million workers. Economic Policy Institute. https://www.epi.org/publication/raising-the-federal-minimum-wage-to-15-by-2025-would-lift-the-pay-of-32-million-workers/

[19] Belman, D., Wolfson, P., & Nawakitphaitoon, K. (2015). Who is affected by the minimum wage? Industrial Relations: A Journal of Economy and Society, 54(4), 582-621. https://doi.org/10.1111/irel.12107

[20] Houseman, S., & Abraham, K. (2021). What do we know about alternative work arrangements in the United States? A synthesis of research evidence from household surveys, employer surveys, and administrative data. Upjohn Institute. https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/OASP/evaluation/pdf/Alternative_Work_Arrangements_Abraham_Houseman_Oct_2021_508c.pdf

[21] Wage and Hour Division. (2008). Fact sheet #39: The employment of workers with disabilities at subminimum wages. U.S. Department of Labor. https://www.dol.gov/agencies/whd/fact-sheets/39-14c-subminimum-wage

[22] Questions and answers about the minimum wage. (n.d.). U.S. Department of Labor. https://www.dol.gov/agencies/whd/minimum-wage/faq#

[23] Abraham, K., Hershbein, B., Houseman, S., & Truesdale, B. (2023). How many independent contractors are there and who works in these jobs? W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research. https://research.upjohn.org/cgi/viewcontent.cgiarticle=1055&context=up_policybriefs

[24] Appelbaum, E., Kalleberg, A., & Jin Rho, H. (2019). Nonstandard work arrangements and older Americans, 2005-2017. Economic Policy Institute. https://www.epi.org/research/nonstandard-work-arrangements/

Nazareno, L., & Liu, C. Y. (2024). The geography of nonstandard employment across U.S. metropolitan areas. Journal of Urban Affairs, 46(2), 319–336. https://doi.org/10.1080/07352166.2022.2053331

[25] MIT. (2025, February 10). MIT living wage calculator. https://livingwage.mit.edu/

[26] Congressional Budget Office. (2023). The budgetary and economic effects of S. 2488, the raise the Wage Act of 2023. https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2023-12/The_Budgetary_and_Economic_Effects_of_S.%202488_the_Raise_the_Wage_Act_of_2023_1.pdf

[27] Somashekhar, M., Buszkiewicz, J., Allard, S. W., & Romich, J. (2022). How do employers belonging to marginalized communities respond to minimum wage increases? The case of immigrant-owned businesses in Seattle. Economic Development Quarterly, 36(2), 108–123. https://doi.org/10.1177/08912424221089918

[28] Willingham, C. (2021). Small businesses get a boost from a $15 minimum wage. Center for Public Administration. https://www.americanprogress.org/article/small-businesses-get-boost-15-minimum-wage/

Reich, M. (2019, February 7). Likely effects of a $15 federal minimum wage by 2024. Congress.gov. https://www.congress.gov/116/meeting/house/108844/witnesses/HHRG-116-ED00-Wstate-ReichM-20190207.pdf

[29] Johnson, E. (2024, February 22). A majority of America’s small business owners support minimum wage increase, even as they worry about worker affordability. CNBC. https://www.cnbc.com/2024/02/22/a-majority-of-americas-business-owners-support-minimum-wage-increase.html

Gutierrez, S. (n.d.). CNBC| SurveyMonkey small business index q1 2024. SurveyMonkey. https://www.surveymonkey.com/curiosity/cnbcsurveymonkey-small-business-index-q1-2024/

[30] Majchrowska, A. (2022). Does the minimum wage affect inflation? Central and Eastern European Online Library. https://www.ceeol.com/search/article-detail?id=1234967

Ahsan, I. (2023, May 18). Minimum wage and sectoral price inflation. Social Science Research Network, 17. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4452506

MacDonald, D., & Nilsson, E. (2016, July 6). The effects of increasing the minimum wage on prices: Analyzing the incidence of policy design and context. W.E. Upjohn Institute. https://research.upjohn.org/up_workingpapers/260/

[31] Nguyen, C. (2011). Do minimum wage increases cause inflation? Evidence from Vietnam. University Library of Munich, Germany. https://EconPapers.repec.org/RePEc:pra:mprapa:36750

[32] Jacobs, K., Perry, I. E., & MacGillvary, J. (2021, January 14). The public cost of a low federal minimum wage. UC Berkeley Labor Center. https://laborcenter.berkeley.edu/the-public-cost-of-a-low-federal-minimum-wage/

[33] Bengfort, H. (2024, April 16). Employee retention: The real cost of losing an employee. PeopleKeep. https://www.peoplekeep.com/blog/employee-retention-the-real-cost-of-losing-an-employee

[34] Reich, M., & West, R. (2015). The effects of minimum wages on food stamp enrollment and expenditures. Industrial Relations: A Journal of Economy and Society, 54(4), 668–694. https://doi.org/10.1111/irel.12110

[35] Jacobs, K., Perry, I. E., & MacGillvary, J. (2021, January 14). The public cost of a low federal minimum wage. UC Berkeley Labor Center. https://laborcenter.berkeley.edu/the-public-cost-of-a-low-federal-minimum-wage/

[36] Cooper, D., Mokhiber, Z., & Zipperer, B. (2021a). Raising the federal minimum wage to $15 by 2025 would lift the pay of 32 million workers. Economic Policy Institute. https://www.epi.org/publication/raising-the-federal-minimum-wage-to-15-by-2025-would-lift-the-pay-of-32-million-workers/

[37] Cooper, D., Mokhiber, Z., & Zipperer, B. (2021a). Raising the federal minimum wage to $15 by 2025 would lift the pay of 32 million workers. Economic Policy Institute. https://www.epi.org/publication/raising-the-federal-minimum-wage-to-15-by-2025-would-lift-the-pay-of-32-million-workers/

[38] Why the U.S. needs at least a $17 minimum wage. (2023, July 31). Economic Policy Institute. https://files.epi.org/uploads/270986.pdf

[39] Lebihan, L. (2023). Minimum wages and health: evidence from European countries. International Journal of Health Economics and Management, 23(1), 85–107. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10754-022-09340-x

[40] Derenoncourt, E., & Montialoux, C. (2021). Minimum wages and racial inequality. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 136(1), 169–228. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjaa031

[41] MIT. (2025, February 10). Living Wage Calculator. https://livingwage.mit.edu/

[42] MIT. (2025, February 10). Living Wage Calculator. https://livingwage.mit.edu/

[43] Downey, N, et al. (2022). Guaranteed income: States lead the way in reimagining the social safety net. Economic Security Project. https://economicsecurityproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/States_Lead_the_Way.pdf

[44] Guaranteed Income Pilots Dashboard. (2025, January 1). Get the latest data on pilots around the country. https://guaranteedincome.us/#pilotschart

[45] Downey, N, et al. (2022). Guaranteed income: States lead the way in reimagining the social safety net. Economic Security Project. https://economicsecurityproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/States_Lead_the_Way.pdf; Economic Security Project. (n.d.). It's more than a check, it's the freedom everyone deserves. https://economicsecurityproject.org/work/guaranteed-income/

.png)