AUTHORS: Nakeina E. Douglas-Glenn, Charity Scott, Chelsie E. Dunn, J. Herman Tomasi, Catherine Auwarter, & Anila Surin

July 2024 [1] [2]

INTRODUCTION

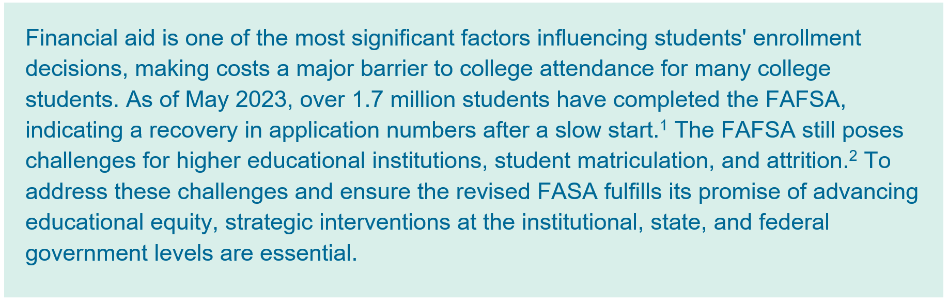

The FAFSA is available to all students regardless of demographic and socioeconomic background, but it is particularly helpful for student groups historically disenfranchised from postsecondary education. FAFSA provides access to subsidized student loans, work-study, Pell grants, and other college scholarships and grants to meet students' financial needs. The average cost of attending college, including tuition, required fees, books, and supplies, is $36,436 per year. As the median family income is $74,580, college costs are almost universally burdensome, especially for disadvantaged groups. The revised FAFSA form aims to increase accessibility and equity but has faced rollout challenges, creating financial uncertainty for institutions and vulnerable students.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- The marred FAFSA rollout is exacerbating extant inequities in higher education enrollment, attrition, attainment, and financing.

- FAFSA rollout in 2023 faced technical glitches and delayed launch, leading to concerns about its effectiveness in determining financial aid eligibility for the 2024-2025 school year.

- Revised eligibility criteria and a simplified application process are expected to benefit millions of students, particularly low-income and minority students

- The New FAFSA form, when fully accessible, will make 1.5 million more people eligible for the maximum Pell Grant.

- Challenges remain in ensuring equitable access to higher education as disparities in FAFSA completion rates persist.

THE PROBLEM

Through bipartisan efforts in 2020, Congress passed legislation for a more simplified FAFSA application. The New FAFSA form was expected to be unveiled by October 2023. However, it was delayed until December 2023 because of technical glitches and incorrect calculations. As a result, students would appear to have more money [assets] than actually true. The Student Aid Index (SAI) calculation guidelines are expected to consider inflation for each year moving forward. The revised means test is expected to capture low-income students and families further. With the formula fixed in January 2024, the first batch of information was anticipated to be ready in March 2024. Instead, the Department of Education reported concerns about inconsistent data provided to them by the IRS impacting 5% of previously submitted applications and an unknown percentage of new applications. This application reformulation was expected to usher in a new era of college access for millions of college students. Instead, the new FAFSA fell disappointingly flat, with many problems still persisting through its ongoing rollout.

HIGH HOPE FOR FAFSA

The new form was expected to increase IRS compatibility with the Department of Education, seamlessly sharing financial data between the institutions. The new form promoted a shorter and more straightforward process (from 108 to 36 questions), thus making it easier for students and their families to navigate the annual pre-college ritual intending to increase the likelihood of a student enrolling in college and persisting to graduation.[3]

The FAFSA revisions are expected to broaden eligibility criteria, capturing students previously excluded from financial aid programs (students experiencing homelessness, formerly in foster care, formerly incarcerated, formerly enrolled in a for-profit college, and students with drug convictions). This fundamentally equitable and wider net will significantly improve access to financial aid for a wide range of students once caught in the crosshairs of societal ills.

The FAFSA revisions are expected to broaden eligibility criteria, capturing students previously excluded from financial aid programs (students experiencing homelessness, formerly in foster care, formerly incarcerated, formerly enrolled in a for-profit college, and students with drug convictions). This fundamentally equitable and wider net will significantly improve access to financial aid for a wide range of students once caught in the crosshairs of societal ills.

The revised forms also anticipate an increase in eligible Pell Grant recipients, expanding its reach to approximately 610,000 new students from low-income backgrounds.

Changes will lead to more families automatically qualifying for the maximum Pell Grant ($7,395). These “income protection allowances” prescribe a generous formula intended to adjust for inflation, protect families' income, and shield more of a student's income from the traditional formula, raising the protected income (20%) of parents, the income of (35%) dependent students, and the income (60%) of students with children.[4] These increases in aid eligibility cannot be understated, considering the skyrocketing rate increase of college tuition since the 1970s.[5] The changes will help address educational disparities felt by several groups, including first-generation, racialized minority students, veterans, and women-identifying students, ultimately increasing diversity on our college campuses.

UNDERMINING EQUITY

The rollout exacerbated higher education access issues. Financial aid accessed through FAFSA plays a crucial role in reducing disparities in higher education attainment.[6] Successful attainment of a degree provides higher earnings and lower unemployment rates throughout a lifetime, with college graduates earning $1.2 million more on average. Early FAFSA filing has been found to lead to higher financial aid awards and an increased likelihood of college completion. However, filing late is associated with a lower likelihood of success in postsecondary school.[7] These delays raise questions about affordability for vulnerable low socioeconomic status, first-generation, women-identifying/gender nonconforming, and immigrant students.

In 2020, as few as 59.7 percent of Asian students and as many as 84 percent of Black students completed the FAFSA, signaling disparities in FAFSA completion rates among different racial and ethnic groups. Given the historically high utility of the FAFSA among minorities and women (74.2%), they are also likely to be heavily impacted by a poorly executed rollout and implementation of the new form, exacerbating existing disparities in access to financial aid and higher education.[8]

IMPACTS AND IMPLICATIONS

A delayed rollout, coupled with many states' “first come, first served” distribution approach, poses another barrier to families whose forms may be late. First-year community college students are less likely to file a FAFSA and are two times more likely than their 4-year public and private counterparts to file their FAFSA late.[9] On average, students who filed later received 60 to 70 percent less state and/or institutional aid than students who filed on time.[10] A system that prioritizes those with quicker access and resources perpetuates the inequality it is designed to minimize, potentially leaving many vulnerable populations under-resourced.

Students with social security numbers could more easily enroll, while parents with ITIN faced barriers. The increase in enrollment in recent years has been due largely (80%) to students from immigrant families.[11] Until recently, mixed-status families, which include children with social security numbers and parents without, were slow to benefit from the form’s revisions.

The decline in FAFSA completions could have significant implications for higher education institutions and student enrollment rates. This is especially true for specialized institutions such as HBCUs and private, tribal, and women’s colleges. These institutions are generally smaller, have limited access to capital, and attract a more targeted student population, making them more susceptible to adverse impacts in a changing financial landscape.

Another critical issue is the number of students who attempt to complete the application but fail to do so because of technical challenges or other barriers. This issue is difficult to quantify, and its full impact may not be known for some time, further complicating the efforts to ensure equitable access to financial aid.

AN IMPERATIVE TO GET FAFSA RIGHT

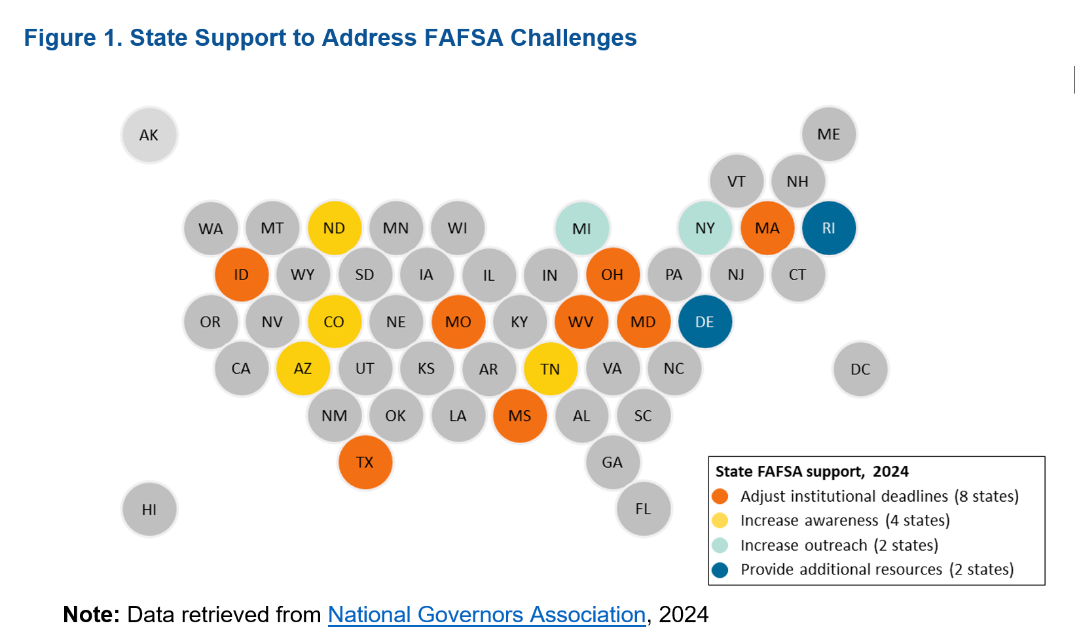

As colleges and universities determine how to provide access and opportunities to students who may be affected until the federal government resolves the form issues, states are stepping in to provide additional resources (DE, RI), increase outreach (MI, NW), raise awareness (AZ, TN, CO, ND), and adjust institutional deadlines (ID, MD, MS, MO, OH, TX, WV) to mitigate the impacts of the delay (Figure 1).[12] As a result, more than 135 colleges and universities nationwide have extended their commitment deadlines.

Federal government measures to remedy the situation include the Better FAFSA Better Future Roadmap tool by the Federal Student Aid (FSA), designed as a resource and training guide for families, schools and institutions, and other stakeholders. A soft launch approach was instituted to address emerging concerns as they arose rather than all at once. Additionally, federal financial aid experts and internal concierge services were dispatched to HBCUs, tribal colleges, and other historically low-resourced institutions for support and training as part of the rollout.[13]

POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS

The FAFSA rollout has left students questioning whether or not to continue their post-secondary education, enroll in a community college rather than a four-year college or university, or begin their post-secondary studies at all.[14] Although community colleges may see steady or even increased student enrollment as a result of this problem, four-year universities and colleges serving many Pell-eligible students may be left scrambling to redeem their enrollment numbers for the 2025 academic year.[15] This issue has created significant financial uncertainty for higher educational institutions and may be significantly altering the life trajectories of our most vulnerable student groups. To re-right these inequitable burdens, we recommend the following:

- Extend the Deadline. Most states adhere to a June 1 deadline for students planning to enroll in college for the 2024-2025 school year. Fewer than 12 states have extended the deadline past this date.[16] States should establish a rolling timeline establishing additional time markers through the end of 2024 to allow more time and assistance for those who have experienced difficulties.

- Deferred Admissions and Flexible Enrollment Options. Flexible enrollment options such as mid-year or rolling admissions should be considered to accommodate affected students. Colleges and universities should implement a plan of action to admit students in the Spring or Fall of 2025, allowing them additional time to secure their financial aid and plan for their enrolment. The offer of guaranteed admission should still be granted with the option to reserve for up to one additional year at current tuition rates.

- Awareness & Outreach. States and higher educational institutions should adopt extant state efforts of awareness and outreach and delayed deadlines.[17] They should do so by targeting currently enrolled students who have received financial aid in previous academic years and partnering with high schools to help admitted students complete the new FAFSA form. They should also use modern social media to meet students and parents in communication approaches they are likely to access regularly. Finally, they should support local community groups with educational outreach experience and interest.

- State Funding for Higher Education. Several states have reported a budget surplus in recent biennium. Funds from the surplus should be reprioritized to support one-time grants to state students. These grants can help bridge the gap created by the delayed FAFSA rollout. States should also establish emergency funds that institutions can draw from to support students facing financial challenges during the academic year.

- Financial Aid Emergency Advances. The federal government can advance funds to states in amounts comparable to historical figures based on anticipated enrollment. This advance could assist colleges and universities in extending offers to students and help universities entice additional undecided students. This is particularly useful for schools without large endowments or those that experience a history of underfunding.

- Federal Government Support. The federal government should continue to support universities serving financial aid-eligible students throughout the summer months,[18] Providing expertise and resources for states and higher educational institutions as they expand their efforts of awareness and outreach to currently enrolled students. The federal government should work with states and institutions to reach out to the high schools of admitted students to ensure successful FAFSA completion and to support their matriculation decisions.

- Universal Grant. A one-time universal federal grant should be provided to all students for the coming academic year, in addition to their financial aid package, in an amount up to the equivalent of the maximum Pell Grant. This one-time grant would make up for the added distress and uncertainty the rollout created for these already vulnerable students and nudge students toward their preferred post-secondary institution and career aspirations. Using the previous years’ undistributed Pell Grants and current funding likely to be left over due to the low FAFSA completion rates make this last recommendation to achieve equity financially feasible.

CONCLUSIONS

The delay in optimizing the FAFSA introduced new challenges the form was designed to resolve, leaving many students and their families stalemated. FAFSA is an entry point for available resources in colleges, universities, and career schools. Completing the FAFSA affords students several benefits, including access to a greater pool of resources at the state and federal levels, improved college affordability, options for loan repayment, and eligibility for loan forgiveness programs. The projected improvements to the FAFSA will undoubtedly have long-term benefits. The increased access will translate into a more educated workforce, higher lifetime earnings, and increased state and federal tax revenue. Institutions at all levels must work together to re-right rollout harms. A combination of targeted measures can mitigate the issues brought about by the launch.

___________

[1] Douglas-Gabriel, D. (2024, April 13). What to know about FAFSA changes. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/education/2024/04/13/what-to-know-about-fafsa-changes/

[2] National College Attainment Network. (n.d.). FAFSA tracker. National College Attainment Network. https://www.ncan.org/page/fafsatracker

[3] Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions. (2020). The long reach of the FAFSA form. Retrieved from https://www.help.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Long2.pdf

[4] Douglas-Gabriel, D. (2023, December 1). FAFSA income allowance protection calculation error. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/education/2023/12/01/fafsa-income-allowance-protection-calculation-error/

[5] Archibald, R. B., & Feldman, D. H. (2012). The anatomy of college tuition. Washington, DC: American Council of Education. Retrieved from https://www.acenet.edu/Documents/Anatomy-of-College-Tuition.pdf

Baum, S., & Ma, J. (2014). College affordability: What it is and how we can measure it. Indianapolis, IN: The Lumina Foundation.

[6] Race and Ethnicity in Higher Education. (2019). Race And Ethnicity in Higher Education: A Status Report. Retrieved from https://equityinhighered.org

[7] Castleman, B. L., & Long, B. T. (2016). Looking beyond enrollment: The causal effect of need-based grants on college access, persistence, and graduation. Journal of Labor Economics, 34(4), 1023-1073.

McKinney, L., & Novak, H. (2015). FAFSA filing among first-year college students: Who files on time, who doesn’t, and why does it matter? Research in Higher Education, 56, 1-28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-014-9340-0

[8] U.S. Department of Education, National Postsecondary Student Aid Study, 2020

[9] McKinney, L., & Novak, H. (2015). FAFSA filing among first-year college students: Who files on time, who doesn’t, and why does it matter? Research in Higher Education, 56, 1-28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-014-9340-0

[10] McKinney, L., & Novak, H. (2015). FAFSA filing among first-year college students: Who files on time, who doesn’t, and why does it matter? Research in Higher Education, 56, 1-28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-014-9340-0

[11] Burke, L. (2023, August 3). Rising enrollment of students from immigrant families. Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved from https://www.insidehighered.com/news/students/diversity/2023/08/03/rising-enrollment-students-immigrant-families

[12] National Governors Association. (2024, April 22). Governors provide student supports to address FAFSA challenges. Retrieved from https://www.nga.org/news/commentary/governors-provide-student-supports-to-address-fafsa-challenges/

[13] Insight Into Diversity. (2023). Education Department launches FAFSA support strategy. Retrieved from https://www.insightintodiversity.com/education-department-launches-fafsa-support-strategy/

[14] Associated Press News. (2023). FAFSA financial aid rollout leaves college dreams in limbo. Retrieved from https://apnews.com/article/fafsa-financial-aid-college-dreams-2023

[15] Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond. (2023). The FAFSA Crisis: Will delayed completions result in enrollment declines? Retrieved from https://www.richmondfed.org/-/media/richmondfedorg/publications/research/econ_focus/2023/q1/q1_2023.pdf

[16] U.S. Department of Education. (n.d.). FAFSA deadlines for 2024-25. Retrieved from https://studentaid.gov/apply-for-aid/fafsa/fafsa-deadlines#fafsa-deadlines-2024-25

[17] National Governors Association. (2023, January 30). Governors provide student supports to address FAFSA challenges. National Governors Association. https://www.nga.org/news/commentary/governors-provide-student-supports-to-address-fafsa-challenges/

[18]Insight Into Diversity. (2023). Education Department launches FAFSA support strategy. Retrieved from https://www.insightintodiversity.com/education-department-launches-fafsa-support-strategy/

Suggested Citation: Douglas-Glenn, N. E., Scott, C., Dunn, C., Tomasi, J. H., & Auwarter, C., Surin A. (2024, July). Equity challenges and opportunities in the revised FAFSA. Richmond, VA: Research Institute for Social Equity. Retrieved from https://rise.vcu.edu/news/news-posts/equity-challenges-and-opportunities-in-the-revised-fafsa.html